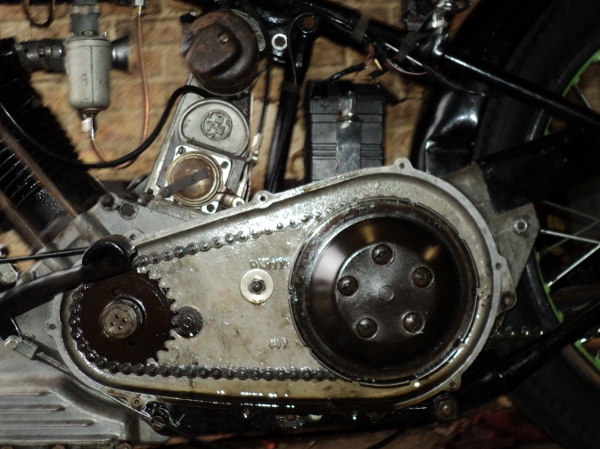

I’ve now got about 70 miles up on the old lady.

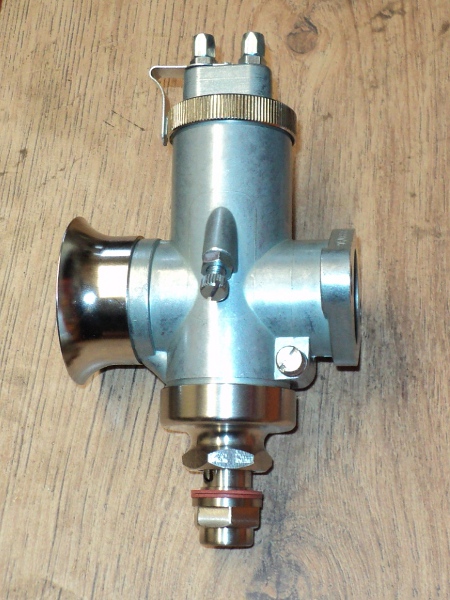

As said earlier she had a Amal Type 276 carburetter fitted rather than the correct Amal Type 89.

Major difference is that the 276 has a smaller bore so the old girl has been undercarburetted.

This model of the carburetter was fitted to the 500cc Panther of this period and I found it was set up as specified for that bike, not only that but it had the same type suffix on the carb body so I suspect that at some time the carb from the other model has been fitted in error.

Having a few miles up now, and on checking the plug finding her running rich even though there is a No.5 slide fitted and the carb set lean, I decided to bite the bullet and get the correct carburetter for her.

Options were to look for a used one or get a modern rebuild.

On checking with Amal themselves I found that the Type 89 was not available but the slightly later Type 289 was.

The difference between them is that the 289 takes its pilot air supply from the main air inlet while the 89 takes it from holes in the side of the body and I decided to opt for the 289.

After a bit of discussion with Amal I ordered a new body less the float chamber, I do after all have a NOS chamber on her now so don’t see the point of getting another one.

The new body cost just over £170 plus post and the inevitable 20% tax .

Two days later a package arrived in the morning post.

In it was a box full of paper shred packing and an “AMAL” box.

Inside that, wrapped in more packing, was a split new Type 289, already jetted and set up for a 1937 Panther M100 with a full “set up and tuning” leaflet plus an envelope containing the throttle slide spring and a new gasket for between the carburetter and its manifold.

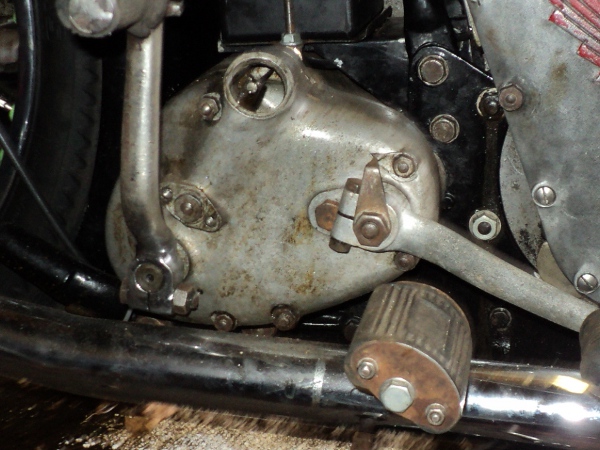

So, out to the garage and fit the new carb.

I had two worries here, the free length available on the throttle and choke inner cables.

First tried was the throttle, and it turned out that there was sufficient free length for the slide to “bottom out”, even when turning the handlebar from lock to lock so no problem there.

But when the choke cable was checked the slide was not bottoming, there was insufficient free length so the cable needed to be altered to suit.

The simple way round this is to shorten the casing of the cable, this has the effect of increasing the free length of the inner cable which is what we want and all that’s needed is an extra 1/4 inch of that free length.

This is one of those fiddly jobs that isn’t often done but if you do know how to do it, it can save you a lot of trouble.

The obvious way is to unsolder one nipple, cut the casing back and then resolder the nipple but this is easier said than done because often solder will not “bite” onto a used cable.

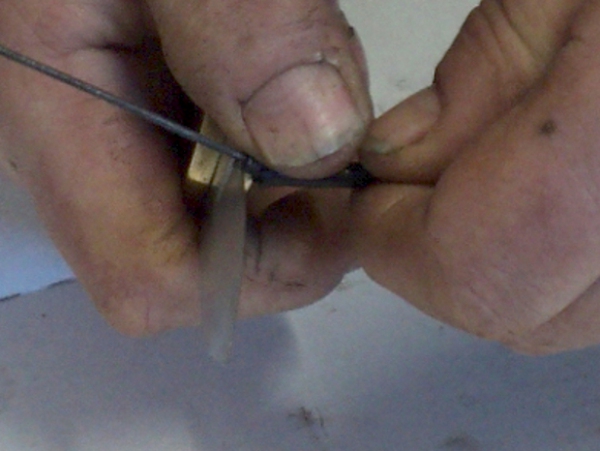

It is however possible to just trim back the outer casing itself without removing the nipple.

To do this you first slide the ferrule back of the end off the casing, up to the nipple and out of the way, this is probably the most difficult part of the process depending on how the ferrule is fixed in place, but using a sharp knife to knick round the casing at the ferrule’s base will normally do the trick.

You can then “winkle” the bit of loose casing cover out of the ferrule and the outer cover needs to be cut back to expose the metal coils anyway.

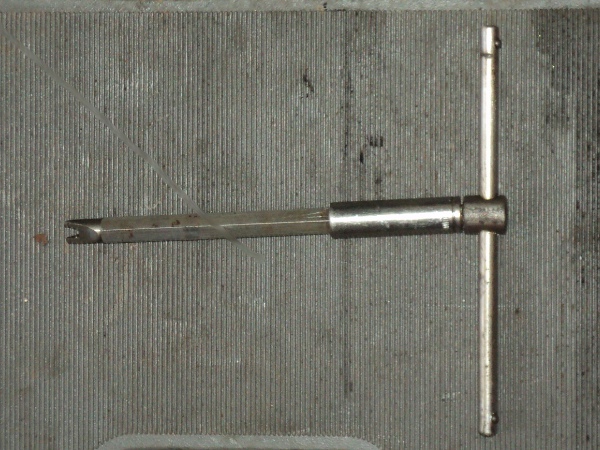

Then, using your knife press the edge of the blade between the end coils of the casing and then twist the blade to lever them a little way apart.

You can then turn the blade so as to take the free end of the coil over the inner wire and the casing can then be unwound away from the inner wire for a few turns.

Once you have sufficient unwound then just nip off the unwound coils with a pair of cutters.

There will be a sharp “rag end” of the casing left projecting, this can be dressed off with a file or careful use of a “Dremel” tool and all that is left to do is slide the ferrule back into place and refit the cable.

I’ve found this trick can be useful at the roadside once when I altered a clutch cable from one make of bike to fit another when its cable broke, meant the bike could complete the event and did not need to be “trailered home”.