The big Panthers are best known as sidecar bikes, back in the 1950’s and 1960’s it was very rare to see one being ridden solo, they normally were seen hitched to a big saloon sidecar such as a Busmar or a Carmobile and they were in fact normally sold as an outfit.

I intend to run mine both as a solo and with a sidecar so I need a sidecar and rather than a big saloon chair I’ve a nice little open sports job that’s based on the Steib S350.

As you can see it’s not in bad condition but a new seat is required. There is one with it but while it is usable it is too bulky and is a poor copy of the original.

A problem is going to come up with fitting it because as you can see it is meant for fitting on the right side of the bike while in UK a sidecar is normally fitted on the left.

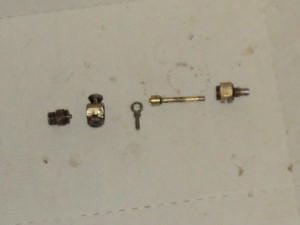

The sidecar is mounted on a Steib LS200 chassis which uses the German DIN standard sidecar fittings and it will mean sourcing a set of bike-side fittings to suit and will probably need a sub-frame to pick-up to that front mounting-point on the chassis.

Besides that the DIN fittings have the beauty that using them means that you have a sidecar that is both quick and easy to remove from the bike, not only that but you do not lose the sidecar alignment settings when you remove it, so when refitting the sidecar you do not need to re-align it.

However, a disadvantage of the LS200 chassis is that it only has a three-point mounting.

While this is adequate for on the smaller bikes (sub-350ccs) that the LS200 was intended for, on a more powerful machine it is better to have the more rigid four-point mounting and it will be necessary to arrange for this.

So, – – Why fit a sidecar?.

Well it means that I can take the bairns with me when I go on events, it gives me extra carrying capacity for luggage and so on, and quite simply, I like them.

Riding a sidecar is totally different to riding a solo, it means learning a new and totally different set of skills but once you can handle an outfit they are great fun to ride, not only that they are great attention getters.